Love in The Time of COVID: The “end” of an era

It has been two years and eight months since the launch of the Love in the Time of COVID international research project. It is time for a new update! This study was offered in 11 different languages and consisted of over 5000 participants from 57 countries. Now, after 16 waves of data, first every few weeks and then every few months, we are preparing to wind down data collection for the project. Soon, we will launch the final survey, at least the last one for quite a while. As such, it is time to again reflect on what we have accomplished together so far.

In our last update, we shared some of the work that has already come from this project. For example, we talked about a paper on how people with lower levels of education faced greater financial and mental health struggles during the pandemic, a paper about how the increase in screentime might have been detrimental to relationships, another about the benefits of a responsive and caring partner during times of stress, and another on how pandemic-related stressors were related to less sexual desire in couples. These papers are now all published and available to be read in top psychology journals.

Since that last post, together with colleagues from around the world, we have continued to work on other exciting projects using the same rich dataset.

- In a project lead by Ana DiGiovanni at Columbia University and Timothy Valshtein at Harvard University, we asked the question: during the pandemic, how are people in long-distance relationships doing (compared to those who cohabitated with their partner)? We compared 775 people in cohabitating partnerships with 630 people in long distance relationships to answer this question. The results challenge the stereotype that long distance relationships tend to do worse. In fact, people in long distance relationships had less conflict and more passion compared to those who lived with their partner. As DiGiovanni put it, “long distance isn’t a vehicle to relationship chaos!” Regardless of the couple status, spending more time with a partner was beneficial for the relationships. However, there were some interesting sub-groups within the sample. Although most people fell into the thriving lovers category (around 70% of the sample) and reported more passion and less conflict when spending more time with their partner, there were also a large portion of fiery lovers (around 23% of the sample), that reported increased passion but also increased conflict when they spent more time with their partner. Only a few (around 3% of the sample) fell into the category of troubled lovers, reporting greater conflict and decreased passion. This suggests that, overall, spending more time with your partner is beneficial to your relationship, but it is not out of the ordinary for some couples to experience difficulties with this.

- In a project led by David Rodrigues from the University of Lisbon, we found that people who are prevention focused (i.e., focused on preventing bad things from happening) were more worried about their own and their loved one’s health during the pandemic. They were also more likely to adhere to preventative health behaviors (e.g., socially distancing). When self-isolating, they also felt worse (i.e., more lonely, more stressed), but only if they did not interact with their social network through alternative means (i.e., online). We concluded that being focused on prevention in threatening times, specifically on isolating oneself from others, can be a double-edged sword: it might help people safeguard their physical health, but isolation may also have negative repercussions on their mental health. However, having a strong social network can serve as a buffer, safeguarding one’s physical health and that of their loved ones without compromising one’s mental well-being.

- In another project also led by David Rodrigues, we found that, single people who were more prevention focused (i.e., wanted to avoid negative consequences from threatening situations) also felt more threatened by the pandemic and reported engaging in sexual activity less frequently. This was true regardless of personality, geographic location, local social distancing policies, gender, and sexual orientation. Similarly to the paper above, being more prevention focused was again a double edge sword: on the one hand, it may have been beneficial to avoid greater close contacts with others given the higher risk of infection, on the other hand, it may have come at the cost of sexual well-being. However, although we did not measure this in our study, other work during the pandemic found that, in a sample of 1559 adults, people diversified and expanded their sexual repertoire (e.g., sexting), meaning that people may have shifted the type of sexual activity they engaged in in order to consider the health risks associated with in-person sexual encounters during the pandemic without sacrificing sexual well-being.

In addition to the projects listed above, we are working on answering other interesting question such as:

How did polyamorous people do in their relationships compared to monogamous people during the pandemic?

Were there some perks (or, potentially, disadvantages) to pet ownership on people’s well-being during the pandemic?

Has boredom been killing relationship passion, but can engaging in new and exciting activities sustain it? For a presentation on this by one of our Love in The Time of COVID co-founders, Dr. Rhonda Balzarini, check out: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1iLQbopi__S9DT0n5arjfZKfmpBY95ll1/view

Are there potential upsides (as well as downsides) to having mixed and conflicting feelings towards a partner?

Were extraverts worse off during the pandemic compared to introverts?

How have parent-child relationships evolved over the course of the pandemic?

Was being able to clearly identify one’s emotions (e.g., anger from sadness) related to better well-being and health?

We are excited about these research questions and can’t wait to share more soon. Our team continues to be immensely grateful to the thousands of participants that have been a part of this project. To those that have stayed with us over these many months: thank you. Because of you, we have learned so much about how people have coped, loved, and connected during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned!

Love in the Time of COVID: 2 years later

March 2022 marks two years since the world changed. It also marks the two-year anniversary of the ‘Love in The Time of COVID’ international research project. When we first set out to study how people were connecting, relating, and coping during the pandemic, we never really imagined just how interested people would be in participating in this research with us. But two years later, we count over 5000 participants from over 57 countries, hundreds of whom have continued to participate month after month, and dozens of research collaborators from across the world. As such, it is time to reflect on what we have accomplished together so far.

The ‘Love in The Time of COVID study started as a bi-weekly survey in March 2020. After 6 surveys, we then switched to bi-monthly surveys, and then switched to every four months. We are now on the 14th survey! This has given us some incredible data to examine people’s experiences not just at the beginning of the pandemic, but also how things have evolved over time. We are so incredibly grateful to all participants, and especially to those who have stuck with us for such long time. If we could, we would thank each and every one individually! In lieu of that, here is an update on how the data provided has helped advance science and what we know about people’s experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- First, in a project led by Dr. Jiang of Rutgers University, we found that people with lower levels of education experienced greater financial distress during the pandemic, and worse mental health. Although the pandemic has been challenging for most people, it has not affected everyone to the same extent, and more attention is needed to protect certain populations. In the words of the main author of this paper, “these results suggest the need to address financial stress related to the pandemic to narrow mental-health disparities among adults from low educational backgrounds.”

- Second, in a project led by one of our ‘Love in the Time of COVID’ co-founders, Giulia Zoppolat of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, we wondered, did an increase in screen time during the pandemic, which helped us all stay connected, also influence people’s romantic relationships? Short answer: yes. We found that people who had greater pandemic-related stressors (lockdown, health worries, loneliness...), tended to use their phone more while in the presence of their romantic partner and also used social media more. In turn, they reported more conflicts in their relationship and worse relationship satisfaction. It is likely that technology can be a detriment when it interferes with quality time with one’s partner.

- Third, in a project led by another ‘Love in the Time of COVID’ co-founder, Dr. Balzarini of Texas State University and the Kinsey Institute, we found that the pandemic negatively affected people’s romantic relationships, but people who had a partner that was responsive to them— who listened, understood, and cared about them – were protected from some of these negative effects.

As the lead author says, “At the very core, these findings suggest that being cared about, feeling valued, and being understood helps. In fact, it might seem too simple, but these qualities in partners might actually be the best medicine we have. They might help make things better even when they can’t be made right.”

- Fourth, in another project led by Dr. Balzarini, we asked, what is sex in the time of COVID like? In this research, we found that, over time, when people experienced stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. health concerns, financial strain), they also reported having less sexual desire for their partner, and this was in part due to external stressors triggering depressive symptoms.

You can read the scientific papers directly above, or, alternatively, check out these pieces in popular media outlets that have covered our work:

- “Will the pandemic ruin your relationship?” in Psychology Today

- “This quality may help protect your relationship from COVID-19 stress” in Psychology Today

- “Expert Advice On Love, Dating, and Pandemic Relationships” in NPR’s Consider This podcast

- “Do you really want to break up, or are you just horny for post-vax summer?” in VICE

- “Caught in a COVID romance: How the pandemic has rewritten relationships” in The Guardian

- “How the pandemic has changed our sex lives” in BBC

- “More sex. Fewer fights. Has the pandemic actually been good for relationships?” in The Guardian

- “Feeling too schlubby to have sex? It’s not just you” In Wall Street Journal

- “If you are dating, the pandemic may have sped up your relationship. So you make it or break it sooner” in Toronto Star

In addition to what is already available, we are working behind the scenes on several other exciting projects. Together with colleagues Anne Harris, Timothy Valshtein, and Ana DiGiovanni from Harvard and Columbia University, Christina Leckfor and Daisi Rae Brand from the University of Georgia, David Rodrigues from the University of Lisbon, Niyantri Ravindran from Texas Tech University, María Alonso-Ferres from the University of Granada, Betul Urganci and Anthony Ong from Cornell University, Pielian Chi from the University of Macao, Lara Kröncke, Mitja Back and colleagues from the University of Muenster, Nipat Pichayayothin Bock from Chulalongkorn University, Christoffer Dharma from the University of Toronto, Dominik Schöebi from the University of Fribourg, Johan Karremans from Radboud University, Anik Debrot from the University of Lausanne, Amy Muise from York University and Francesca Righetti from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, we are pursuing the following questions (and more):

- Did people in long distance relationships (LDRs) experience more or less conflict and passion in their relationship compared to those not in LDRs?

- Is Zoom fatigue real? And why do we feel it?

- Who is more likely to engage in health-protective behaviors like social distancing?

- Are extraverts really suffering more than introverts?

- How are parents doing?

- Has boredom been killing relationship passion, but can engaging in new and exciting activities sustain it?

- Can affectionate touch help romantic relationships during stressful times?

We are excited about these research questions and can’t wait to share more soon. To all of our research participants: thank you, this would not be possible without you. A big shout-out also to all of the research assistants, led by the incredible Megan Tracy, who have also been working tirelessly behind the scenes to make this all run smoothly.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned!

Excited and nervous: Mixed feelings as the pandemic evolves

Despite the excitement and eagerness people expressed when listing all the things they were looking forward to doing, people also expressed some mixed feelings when thinking about the end of the pandemic or the easing up on the restrictions and regulations and a return to more “normalcy.”

Giulia Zoppolat, Rhonda Balzarini, and Richard Slatcher, Love in The Time of COVID Project

In the latest survey of the “Love in The Time of COVID” project, our ongoing international study of how people are connecting, relating, and coping during the pandemic, we were curious to understand how people were doing one-year in.

We asked participants the following question: what are you most looking forward to when the pandemic is over? The answers are touching, relatable, and very interesting. It is safe to say that most people are exhausted and ready for the pandemic to be over. As can be seen in the word cloud made from the hundreds of answers we received, which illustrates the most mentioned words by highlighting them in larger text, repeating themes and commonalities emerged.

People seemed to express a collective longing and deep yearning for similar important aspects of life, for “normal every day things that we haven’t done since the start of the pandemic,” as one participant put it. Most people’s answers included mentions of wanting to see and be with their loved ones in person (hugging in particular was mentioned over and over again), some they haven’t seen in almost two years, and to make up for skipped celebrations and gathering (e.g., birthdays, graduations, wedding, family reunions but also funerals). Many people listed a series of social and cultural events and spaces they were looking forward to frequenting again, such as concerts, museums, theaters, bars, clubs, restaurants, cafes, shops, and sporting centers. They looked forward to going out with their partner or starting to date again, to having deep conversations with friends, and also casual chats with strangers. People especially mentioned looking forward to being able to do these things without feeling worried about contracting COVID-19 and the constant fear and anxiety that accompanies that (people said things like, “I look forward to not having COVID anxiety that seems to live just below the surface. That thought that hits once or twice a day of ‘What if I or someone I love gets COVID?’”). Many mentioned looking forward to travel, to seeing old friends, visiting familiar places, and also to discovering new things. Some people even said they look forward to being spontaneous again and to leave the repetitiveness of their current rhythm behind. One participant captured the tediousness of their current life quite vividly, stating that they look forward to:

“Eating out and not doing dishes or buying the food or cooking the damn food or picking up the groceries for the food or contributing a single bit of emotional energy to plan out the damn food.”

Despite the excitement and eagerness people expressed when listing all the things they were looking forward to doing, people also expressed some mixed feelings when thinking about the end of the pandemic or the easing up on the restrictions and regulations and a return to more “normalcy.” People are, in fact, also feeling nervous, especially about having physical contact with others. While people say that they mostly look forward to time with family and friends, spending time in larger crowds (e.g., at bars, parties, concerts, or sporting events), is something people are quite nervous about. When we asked about their social life after the pandemic is over, about 50% of people said that they find the idea of having a busier social life more overwhelming than not.

There is a lot for people to adjust to, and in some cases, it turns out, there are some things related to the pandemic that people are apprehensive about leaving behind. For example, when about 70% of participants said that there was something about their life during the pandemic that they would miss. Here too, as the world cloud below illustrates, people’s answers reveal some common themes.

Many answers revolved around work, and particularly the benefits for those working from home. For example, people appreciated nixing the commute (no more traffic stress and more sleep!) and the extra personal time that this allowed, along with avoiding small talk with colleagues, the pressure of the office environment, and the ability to prioritize comfort when picking out the daily outfit. Many people mentioned they will miss the slower pace of life they had during the pandemic, a less scheduled and frenetic calendar, and the lack of social pressure and expectations to do things. People seemed to have been able to simplify their life and prioritize things that mattered more and cut out the noise. Several people mentioned that while they had lost touch with certain friends or acquaintances, their closest relationships got stronger as they found ways to stay connected during the pandemic. People seemed to appreciate the lower quantity of relationships and activities to keep up with, the slower pace that that afforded them, and the ability to focus on the fewer deeper connections they cared about as well as hobbies or activities they intrinsically enjoyed. As one participant put it, “My life has slowed to a nice pace. I’m afraid of the hustle and bustle of ‘normal’ life.”

(It is important to note that there are strong social/economic moderators that are likely at play here, as people who experienced greater stressors due to the pandemic, such as having to take care of sick loved ones or small children, losing a job or having to continue physically going to work, is much different from those who didn’t experience these stressors. Our research team is currently investigating these points).

Interestingly, a thorough read of responses suggests that people are not experiencing one or the other, but both — people are both looking forward to life after the pandemic and are nervous about it, there are things they very much are longing to do again but also things they will miss. As we cope with these mixed emotions and experiences, it is important to remember that these are understandable and quite widespread feelings. As the commonalities in the responses to our survey questions show, we are not alone in both our excitements and our fears.

Love in the Time of COVID project – a 9 month update

Nine months have now passed since the “Love in the Time of COVID” project launched, just two weeks after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic in March. In these nine months, more than 5000 people from 57 different countries have shared their experiences with us, repeatedly answering questions about their emotional and relational life. Thanks to their time and dedication to the project, we now know more about how people are connecting, relating, and coping over the course of the pandemic. With this post, we would like to offer an update and a little overview of the project. This post is also a thank you to our participants who continue to selflessly dedicate their time to this important study. None of this would be possible without your contribution!

How have people been doing since we launched the “Love in the Time of COVID” project in March 2020?

It comes as no surprise that people’s lives have been impacted by the pandemic. Among all respondents, the overwhelming majority (88%) indicated that their lifestyle had considerably changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic with only 12% of people reporting no changes to their lifestyle. But how were people reacting emotionally to these changes?

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when people were asked how distressed they had been feeling, most said they were “a little distressed.” The second most common response, however, was “quite a bit distressed.” This was not surprising, as people in great numbers all over the world were starting to deal with new difficult circumstances, such as the sudden loss of employment and social isolation. In our survey alone, over 300 people reported losing their job due to situations related to the pandemic, almost 40% stated that their financial situation had been negatively impacted by it, and the majority had not seen a friend in person for the two weeks before the first survey. These factors are all important ingredients for emotional distress.

Fast forward three months later, and the situation looks a bit different. While many people were still feeling distressed, most people indicated that they were “a little bit distressed” or “very slightly or not at all distressed.” In other words, people were feeling less distressed than they were at the beginning of the pandemic.

Were people less distressed because they thought the end of the pandemic was in sight? No. When we first asked in March how long they thought the pandemic would last, most thought it would last six months to one year. The second most common response was that the pandemic would last three months. But when we asked them again, three months later, the most common response was that the pandemic would last one to two years, followed again by six months to one-year. In other words, people expected the pandemic to last much longer than they originally thought, but were less distressed than they were at the beginning. This might suggest that people are emotionally coping with their new circumstances, despite the finish line looking farther away.

Why would people be both less distressed and at the same time think the pandemic would last longer than originally anticipated? We don’t yet have an answer to this question, but there are likely a variety of factors at play. For example, advances in the scientific and medical understanding of the virus and possible treatments may have alleviated some fears and concerns. Another possible reason for why people seem to be doing emotionally better is that humans are incredibly resilient beings and have an astonishing capacity to face hardships in life, from the smallest to the most extreme. We are able to quickly adapt to new and difficult circumstances. During the pandemic, people may have experienced the initial distress and hardship due to things like loss of incomes, restricted movement, health worries, difficulty in planning for the future, but quickly employed various strategies and coping mechanisms to handle the situation. For example, people migrated in great numbers towards online platforms to continue connecting with family and friends while social distancing, and also spent considerably more time out in nature than before the pandemic. Indeed, our results show that 25% of people reported spending no time outdoors at the onset of the pandemic, whereas only 6% reported not spending any time outdoors three months later. Given the importance of social ties and nature to our well-being, people seemed to be employing helpful strategies during stressful times.

Another reason people may be feeling less distressed over time is that people have a tendency to become less alarmed by risks as time goes on, even if the risks persist. Given that people are notoriously bad at calculating risks, especially when it comes to themselves, people may have perceived higher risk at the beginning of the pandemic and then slowly readjusted their sense of emergency and threat without necessarily being aware that they were doing so. This process is aided by a variety of psychological biases, such as positivity bias that leads people to believe that a negative event – such as having severe reactions to COVID-19 or losing a loved one due to COVID-19 – is less likely to happen to them than it is to others.

In response to the first survey in March, 37.2% of people said they were either worried a lot or completely worried about getting or having COVID-19, compared to 25.7% of people three months later. In March, 28.6% of people said they were only a little worried or not at all, compared to 42% of people six months later. In other words, as time went on, people became less worried about getting or having COVID-19, despite the increase in deaths worldwide.

People also became less worried over time about their friends and family getting COVID-19. However, in all six surveys analyzed here, people were consistently more worried for their loved ones than they were for themselves. This is consistent with research indicating that people tend to be more concerned about the risks for their loved ones than for themselves. This is usually out of love and concern for others, and partly because people tend to imagine worse outcomes for others than for themselves and because they have less control over other’s behavior than their own.

It is important to note, however, that the numbers and statistics represented here are averages across all participants. While on average people seem to be doing emotionally better over the course of the pandemic then they were at the onset, the pandemic has not hit everyone to the same extent. For example, people who have financially suffered from COVID-19 also reported being more distressed than those whose financial situation had been less impacted. This is not surprising, as financial difficulties have a tremendous impact on people’s lives and emotional stability. Therefore, while people reported being less distressed and less worried about getting or having COVID-19 as time went on, this may also reflect the fact that some people have simply been hit less hard than others.

What does all this mean for love in the time of COVID-19? To be honest, we’re not sure yet, but that’s why the continued involvement of the participants in this research means so much to us and why we wanted to give you a quick snapshot of how people have been feeling over the course of the initial phases of the pandemic. We are incredibly grateful to the participants who have given their time and energy to this important study. The pandemic is not yet over, and neither is the Love in the Time of COVID project. The research team is currently working on examining a variety of research questions and writing up the findings in papers that will be shared with the research community in online journals and with the wider community here on our blog. We are looking into questions like: how has the increase in technology use influenced people’s relationships? How are parents dealing with the stress of managing work and childcare at home? What is Zoom fatigue and how is it affecting us? Have people’s sexual behaviors and relationship quality been affected by stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic? Stay tuned for more.

For further readings:

An interview on resilience during COVID-19 with Dr. Ann Masten, resilience researcher.

New York Times article on why people aren’t so good at risk assessment and what biases may be coming into play when calculating personal risk during the pandemic.

Listen to this podcast where Dr. Slatcher, one of the Love in the Time of COVID team members, talks about more findings from the project.

Read a pre-print (not yet peer reviewed) by our team of researchers on how responsiveness from a partner can help alleviate the difficulties that COVID-related stressors place on romantic relationships.

Are extraverts really suffering more than introverts?

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have heard a lot about the particular suffering being endured by extraverts. But are they really suffering any more than introverts?

Photo by Kinga Cichewicz on Unsplash

Since the pandemic began, I have seen a lot of tweets like these:

The logic behind these tweets goes something like this: 1) extraverts like to be around people (true), 2) people are spending a lot less time around others because of social distancing (also true), and 3) because of these two truths, extraverts must be suffering more than introverts right now.

But we really don’t know whether or not this last piece of logic is true. Why? Because this is the first time in history that massive numbers of extraverts and introverts all around the globe have been socially isolated—or, at least, the first time that this has happened since researchers started measuring introversion/extraversion in any meaningful way.

We now have some data to try to get a little closer to the truth of whether extraverts are suffering more than introverts during the COVID-19 pandemic. I’m going to walk through several analyses that I recently conducted from the Love in the Time of COVID research project. These data were collected during the two-week period of March 27-April 10, 2020, when many U.S. states and European and Asian nations had recently begun social distancing. There were 2,580 respondents who completed our survey (a map of where those respondents came from can be found here).

We assessed extraversion with the BFI-2-XS (Soto & John, 2017). Respondents were asked to indicate, on a 5-point scale, how much they agree or disagree with the following statements about themselves: “tends to be quiet” (reverse-scored), “is dominant, acts like a leader,” and, “is full of energy.” It’s a short measure, but a well-validated and reliable one.

Here’s how our sample looks in terms of levels of extraversion/introversion:

As you can see, there are more extraverts than introverts, but there are plenty who score at or below the mid-point (i.e., introverts).

So that we can make sure that we are looking at those who are most likely to be social distancing, I selected those who indicated that social distancing had been ordered in their community, a total of 1,899 people in our sample.

I first looked at the correlation between extraversion and things that most would probably agree are indicative of suffering: feeling socially disconnected, lonely, isolated, feelings of distress, irritability and depression. The correlation table showing links between extraversion and these indicators is below.

Okay, so what do we see here? If the hypothesis that extraverted people are suffering more from social distancing is correct, we would expect a positive correlation between extraversion and our suffering indicators. That’s not what we see. Extraversion has zero, and I mean zero, correlation with feeling more or less connected with others as a function of the COVID-19 pandemic. This means that levels of extraversion/introversion appear to have no bearing on how socially connected people feel during the pandemic.

For the other suffering indicators, we see small but consistent negative correlations with extraversion. The more extraverted people are, the less lonely, isolated, irritable, distressed and depressed they reported feeling over the prior two weeks. So, if any group appears to be suffering more here, it is introverts. Later on in this post, I speculate about why this might be.

Included in the roughly 1,900 people in this sample are a lot of people who live with others (1,591 people) and fewer who live by themselves (301 people). “Aha!” you might be saying to yourself, it’s really those extraverts who are living alone who are suffering. We know that those living alone are suffering more than those living with others, so perhaps it’s the extraverts in that group that are especially suffering. This would be a reasonable hypothesis.

However, we see the same pattern effects for those who live alone as we do for the sample as a whole:

And for those who live with others:

These data indicate that people who are more extraverted—whether they live alone or live with others—are decidedly suffering less than those who are more introverted.

The next question you may be asking yourself is why are extraverts suffering less than introverts? Well, we know that extraversion is a protective factor against depression. So we would have to see the negative association between extraversion and depressive symptoms that we usually see completely flip if extraverts were suffering more.

We also know that the happiest people tend to be highly social and maintain close social ties. In our data, we see that extraverts are Zooming more (i.e., using video chat) than introverts:

In addition, extraverts are exercising and spending more time outdoors than introverts:

Both exercising and spending time outdoors have been shown to be associated with greater well-being.

So, in a lot of ways, it’s not surprising that extraverts seem to be suffering less than introverts during this time of social distancing. They have a slight advantage in warding off depression to begin with, are Zooming more in the pandemic, exercising more, and spending more time outdoors.

Interestingly, controlling for extraverts’ tendency to Zoom more, exercise more, and spend more time outdoors does not diminish the associations (at all) between extraversion and indicators of less suffering in this sample.

Does all of this mean that the people who say that extraverts are suffering are completely off the mark? Not necessarily. My hunch is that perhaps those who are more extraverted are suffering more now compared to how they were before the pandemic. This is what behavioral scientists call a “within-person” effect, in that we would be looking at increases in suffering within extraverts from before the pandemic until now (or from now until later in the pandemic, when people might be suffering even more—we will be able to test this idea in the weeks to come).

It’s also possible (probable?) that we might see an equivalent increase in suffering among introverts over time as a function of social distancing. The need to be around others is a fundamental human need. Although extraverts like to go to parties more than introverts and like to talk more (especially in large groups) than introverts, that doesn’t mean that introverts don’t need to be around people.

So, the message for now, if anything, should be: Look after your introverted friends and family, because they may be suffering (but probably only slightly more than extraverts are).

How socially connected are people feeling?

It’s been three weeks since we launched our Love in the Time of COVID research project. Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, we plan to share important findings with the public as quickly as possible. This blog will be one of the first places that we share our findings.

Photo by Gabriel Benois on Unsplash

It’s been three weeks since we launched the Love in the Time of COVID research project. Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, we plan to share findings with the public as quickly as possible. This blog will be one of the first places that we share those findings.

The analyses presented below were conducted on April 9, 2020 (data collected March 27-April 9). As of April 9, 2,060 people had completed our survey. Since our translations of the survey have started coming online, we now have roughly double that number of respondents in the study.

Here is where those 2,060 people come from (at the town level, map courtesy of UGA demographer Jeffrey Wright):

https://heffaywrit.carto.com/viz/9c9b3802-18f5-42c6-b1ee-2cfef4aced8d/public_map

As you can see, we have pretty good global representation, though our sample is over-represented by participants from the U.S. and Europe. It will be great to get more participants from Africa, Asia, South America and Oceania as more translations of the survey come online (the survey is currently available in 9 languages).

So our first big question is: How connected are people feeling with others right now?

Roughly 25% of people are actually reporting feeling more connected than usual. This is pretty interesting. I think that this is probably a function, for some, of 1) feeling like the whole world is in this together, and 2) because a lot of people are using Zoom and other video chat software to connect to people they haven't talked to in a long time. My wife, for example, hasn't talked to some of her cousins in years. Now she and her four sisters and their three cousins and both of their moms are Zooming every other week.

However, troubling effects are seen on the left side of the graph. More than 50% of respondents felt less connected with others over the past two weeks.

We will no doubt see haves and have-nots, socially, over the course of the pandemic. A reasonable prediction is that many of the haves will be in living situations with others that were already good to begin with (good relationships with spouse, kids, roommates, etc.).

Among those who are in romantic relationships that are already high in conflict, boring, or dissatisfying in other ways, I think they will end up being pretty unhappy (more than they already are in their relationships). We've heard that the divorce rates in China have gone up the last several weeks. If this effect bears out with more data, I think the effect is a function—at least in part—of those in dysfunctional relationships having to spend a lot of time in the middle of that dysfunction. In contrast, among those in good relationships at home, and among those who are fortunate enough to be able to work from home, I think we will see many feel more connected.

What do the data say so far? Let’s look at those couples on the higher end of relationship satisfaction (score of 6 or 7) compared to those who score a 5 or below on a 7-point relationship satisfaction measure.

Do people who are less satisfied in their relationships feel more or less connected to their partner since the pandemic began? We see a fairly normal distribution in their answers

A great many of them are feeling depressed. Generally (i.e., in non-COVID times) we see strong links between marital dissatisfaction and depression, but still, this graph below is pretty striking.

What about those in happy relationships, in terms of how connected they have felt to their partner since the pandemic began?

Whoa!

Nearly 50% feel more connected to their romantic partner since the pandemic began. This reminds me of Eli Finkel’s All-or-Nothing Marriage idea, in which the really best relationships thrive, given the right circumstances. Having a lot of time cooped up together may be giving happy couples more oxygen, to use Finkel’s analogy, and may feel closer than ever during the pandemic. It will be very interesting to see if this effect changes over time.

Let’s get back to how people in our sample are generally connecting with other people while in isolation. As you can see from the graph below, roughly 85% of the whole sample are connecting with friends on video chat to at least some extent. Over 35% talk to friends through video most days or every day. That the majority of people in our sample are virtually connecting with others is good news.

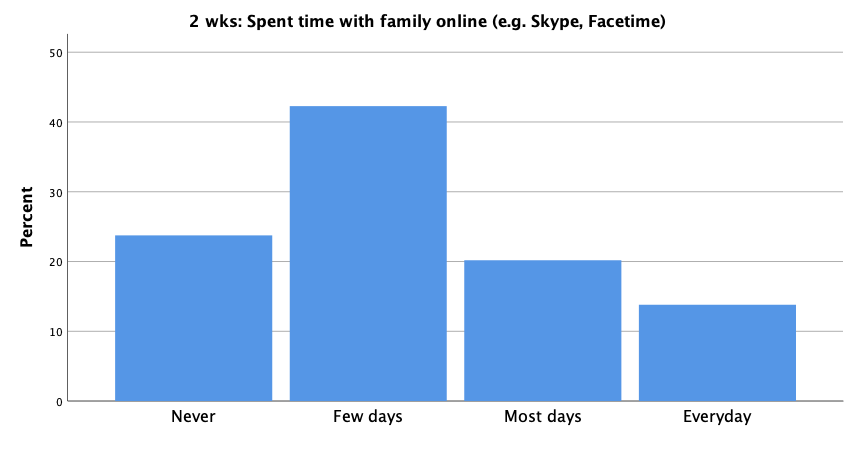

We see a similar pattern when we look at spending time virtually with family:

An important caveat: We are not capturing in our sample those who do not have access to the internet. The social challenges facing those who cannot connect virtually with others, especially for those who live alone, will be high.

I’m curious to find out if we will see a Zoom fatigue effect if social distancing goes on for several weeks (or months). In a recent paper, David Sbarra, Julia Briskin and I argue that people are evolutionarily hard-wired to really connect with people in small groups of 2-4 rather than big ones.

I predict that when people use Zoom to talk to just 1-2 other people at once, they will feel more connected than those using it in larger groups. Larger Zoom calls are like a seminar in which only one person can talk at once. It's just not how people normally talk at social gatherings. With 1-2 other people, a video chat much more closely approximates an in-person interaction. We plan to ask respondents in our study about Zoom fatigue in the weeks to come.

One of the important things to look at as we go forward is whether the pandemic is hitting people who are living by themselves much harder than those who are living with others (spouse, family, roommates, etc.). In our sample, 16.4% live alone while 83.6% live with others. 28.9% of those living alone report feeling quite a bit or extremely lonely. In comparison, 21.1% of those living with others feeling quite a bit or extremely lonely. This is a non-trivial difference in loneliness.

Given the effects of loneliness on morbidity and mortality (see Julianne Holt-Lunstad’s important meta-analysis on the topic), these are numbers we will want to watch closely over the next several weeks.